The Hot Potato Machine

Jack's alive, and likely to live

If he dies in your hand, you've a forfeit to give.

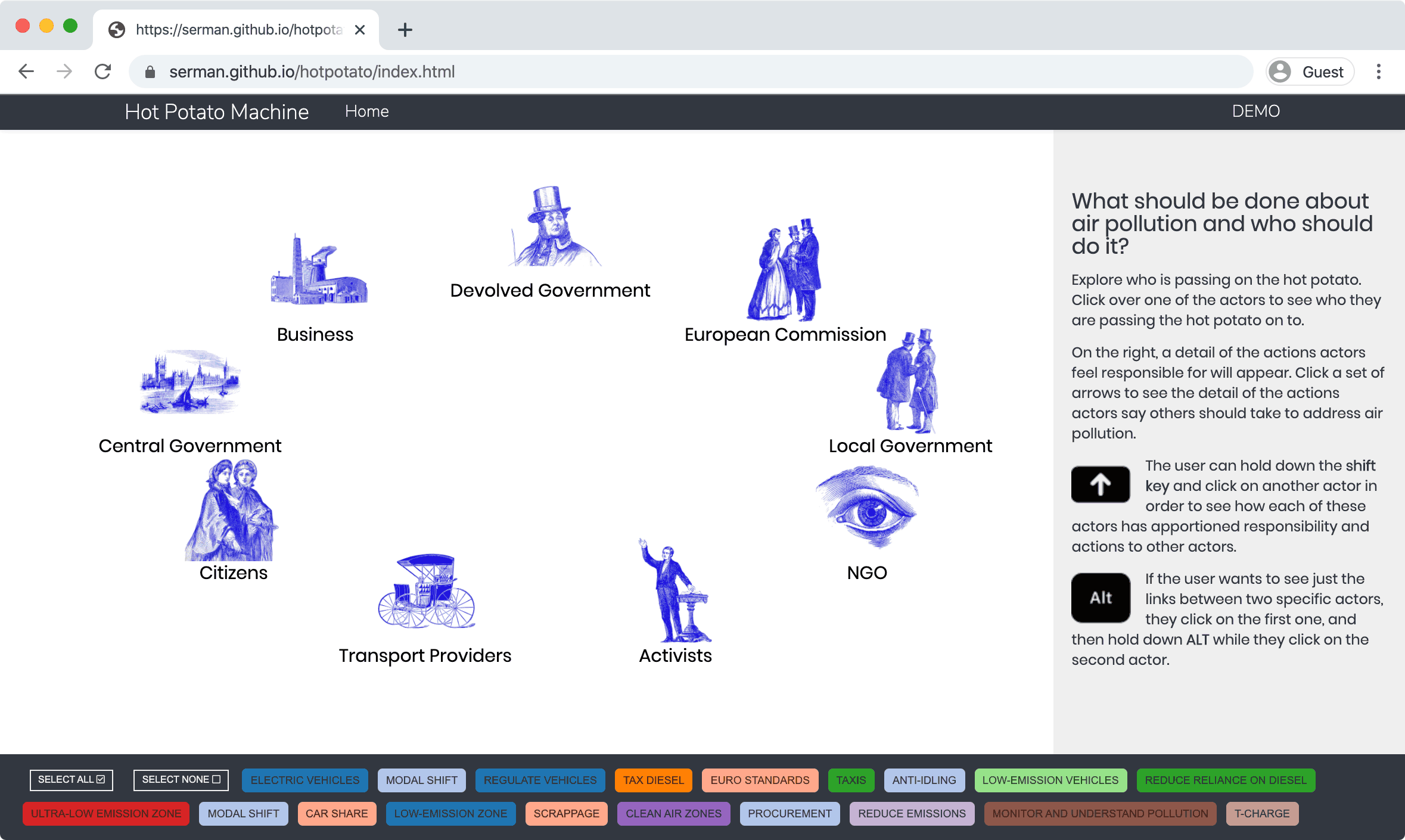

The version of the “hot potato” game recorded in 1888 was played with a candle but the premise remains: don’t be the one to get caught out when the music stops. Some issues are passed around in the same way. Who is passing the hot potato of air pollution to whom? Who is responsible and who needs to take action according to whom? Does everyone tell the same story? In this project, we wanted to understand and visually explore different ways of responding to and apportioning responsibility for complex issues such as air pollution. Taking cue from Bruno Latour’s call to “follow the actors” (2007) the Hot Potato Machine was envisaged as a way to follow what different actors say about each other in relation to how to tackle air pollution. Rather than focusing on measurements of pollutants, we were interested in how digital data might tell us about different ways of seeing air pollution as an issue, different imagined solutions, the fabric of relationships around it, and where there might be tensions, differences, knots and spaces for movement.

As a test case, we created a prototype of the Hot Potato Machine starting with statements from actors engaged in the issue of air pollution in the London Borough of Camden. Following these statements soon took us to statements at different scales, including to the level of the Greater London Authority and the UK as a whole. Our prototype focuses on a specific “issue story” revealing different views on who is responsible for reducing air pollution from diesel taxis. In order to further extend this work we have developed a worksheet for collecting this kind of data in relation to other locations and issues, which may be used in the context of teaching, research, advocacy or public engagement activities.

GO TO SAMPLE DATA USED TO BUILD THE PROTOTYPE

Relation to the co-creation processes in SaveOurAir

Our preparation for the first Save Our Air data sprint in London introduced us to the contentious political landscape of air quality. In July 2017, the Departments for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and Transport (DfT) published the “UK plan for tackling roadside nitrogen dioxide concentrations.” Critics specifically accused the government of abdicating responsibility for tackling air pollution to regional and local government (Barnes et al, 2017). Advocacy group ClientEarth argued that government was “passing the buck” (ClientEarth, 2017) and the Local Government Association called for increased funding for local interventions and more national policies (LGA, 2018). London has itself been a site of high-profile finger pointing. On the one hand, the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has been accused of insufficient action (Barrett et al, 2017) and on the other, he claimed that the national air quality plan lacked the “ambition” needed to support his work in London. This led us to think: might they be passing responsibility for air pollution like a hot potato? We became interested in how air pollution activists engaged with a range of actors – including government, civil society and businesses – and in particular how part of their work seemed to be to transform gridlocks of blame and standstill around air pollution into virtuous cycles and mutually reinforcing eddies of action. We were also fascinated at how an apparently local incident could be so interconnected to so many other societal settings, such that a story would travel from individual decisions in street scenes through to car manufacturers and regulators, tabloids and teachers, scientists and politicians, and back again. The idea for the tool emerged from an attempt to map the different routes to address air pollution at a local level. We used a hypothetical site of poor air quality in Camden as a launchpad to position activists in relation to the government, business and citizen-led interventions. As we plotted these actors, we identified many differing types and sites of intervention from targeted behaviour change interventions at hyper-local level to national policy initiatives, as well as actors implicated across them. Reviewing such a complex and varied field of possible policy initiatives, we asked:

- Who do actors say is responsible for tackling air pollution? And what do they say these other actors should do?

- How can data about what actors say about each other reveal controversies around air pollution? And what might visual representations of the fabric of responsibility do in relation to the issue?

In Copenhagen, we met with the City of Copenhagen's Solutions Lab as well as social researchers (such as Anders Blok), who raised questions about how the project could be kept up to date as well as which sources to focus on. These discussions led us to focus on policy documents for our prototyping work. We also returned to Camden Air Action and Camden Council to present the Hot Potato Machine, and received useful feedback. One of the activists commented:

“You begin to see that it’s a massive problem that it isn’t clear where the responsibility lies – there is not one place and this is one reason that nothing has been done. There isn’t a minister you can pin this on. It’s Department of Transport, it’s DEFRA, it keeps on moving. With air quality, when it wasn’t a hot potato, there was never a reason to do anything about it. It was passed on to DEFRA but they passed it on. The potato has got to get hot before anyone puts any effort into it, and deals with the institutional contributions.”

She suggested the tool was “relevant and novel” and could be useful for activists to consider “who does do what, and where campaigning energy should be directed”. She also thought it could be “potentially very interesting especially for officers at Camden because they will want to understand how to mobilise people”. She also emphasised that it would be particularly useful if it could be kept up to date.

The user/public context

As we developed the prototype, we were considering how it might be used by activists, journalists, public servants, researchers, students and other publics who are already interested in or engaged around the issue of air pollution, as a means to consider how different actors apportion responsibility around it. We started with air pollution as an issue, but as the project progressed also became interested in how to follow chains of attributed responsibility around associated issues, policies and activities.

This approach to mapping a public policy issue can help to draw attention to wide variety of different actors associated with it, as well as their various activities. The project is intended to map what is said (as well as what is not said) around the apportioning of responsibility for an issue. Drawing on previous research on issue mapping and controversy mapping, the idea is to visually explore who speaks about whom and what they hope will happen, as well as who are the dominant and marginal actors. As well as drawing attention to “issue work” around air pollution, it may also highlight shared or divergent visions of responsibility and action. We were interested to see what it would like to visually overlay these different visions and imagined futures, and to see whether activists or public servants might use it to identify blockages or opportunities.

This approach could be used to tell different stories about air pollution. Rather than focusing exclusively on air pollution hotspots and “thin descriptions” (Porter, 2012) of pollutants and polluting activity, such stories could also incorporate the social, cultural, political, economic, institutional and other contexts which both give rise to and respond to air pollution as an issue. These stories could be used by activists, journalists or public servants to explore different collective responses to air pollution, as well as telling “stories about stories”. We are also interested in developing the Hot Potato Machine for use in the context of teaching, research and public engagement activities with our colleagues and students in universities, and beyond.

The data used in the project

We wanted to map public statements by actors across government, business and civil society. To this end, we started by collating, querying and extracting data from policy documents, consultation responses and position papers. As a result of the UK’s digital and public sector information policies, many policy documents and reports are available online (Owen et al, 2013).

In order to get started we began with a very simple querying strategy. We wanted to see how far we’d get by simply “following the actors”, and started “in the middle” of things with a small set of actors and their claims. As actors mentioned

other actors, we recursively added them to the list and then looked for documents, websites, claims and plans where they mentioned others, and recorded those claims. As such, in order for an actor to make it onto the list they had to be

mentioned by someone else. This is comparable to “snowball sampling” in social research, and also what has been called “associative snowball querying” (Rogers, n.d.). There were a number of querying strategies that we used in order to build the

corpus of materials and claims that were searched. For example we used “site searches” such as [site:camden.gov.uk “air pollution”] in order to query the websites of actors who were mentioned to identify further claims of

responsibility about

air pollution.

Our initial exploratory data collection is available here. Having used this data to identify a specific controversy around diesel taxis, we then focused on gathering a subset of data focused on this specific issue. We have developed a worksheet with further considerations for assembling and coding data for the Hot Potato Machine, which may inform subsequent work in this area. This can be found at this link.

The ‘situating techniques’ used to make data-stories local

We started our data story by focusing on air pollution within Camden. As soon as we started doing so we found (perhaps not unexpectedly) that the council’s activities were deeply entangled with London-wide and national policy and advocacy activities. The “local” could not so easily be disentangled from other scales and levels at which action around air pollution is coordinated. We hoped to make it easier to follow these circuits of action, involvement and imagination in order to obtain a different perspective on air pollution that occurs in streets, squares and local situations. In querying for materials, we also observed the prominence of actors doing “issue work” around air pollution at the level of the city or the country, rather than on specific places or regions within cities. As such while we started local, by following actors and documents we soon found ourselves in other places and at other scales. For our proof of concept we ended up focusing on the issue of diesel taxis rather than a locale in order to illustrate the approach.

So far we have focused mainly on data assembled from digital documents and websites using a combination of querying strategies and what has been called “search as research” (Rogers, 2013). For further work we are particularly interested in the role of digital technologies, platforms and the web in providing different kinds of online spaces in which claims of responsibility are made, and to account for how these may also contribute to shaping who is prominent and who is marginal, who is represented and who is absent. One methodological issue is account for how “the local” is done in these different spaces – e.g. through combinations geolocation services, keywords, hashtags, accounts, links, likes and recommendation engines – which provide different ways of understanding and interacting with issues at a local scale. For example, one might take the approach of the Hot Potato Machine to see who is mentioned in relation to air pollution using data derived from social media platforms, local news and other sources.

What have we learned from the process?

Assembling data about who is responsible for an issue according to whom can be a time consuming process, but also a rich and informative one. There are some important decisions required in the design process about how to gather data, where to start, what to focus on and whether and to what extent to make different claims commensurable (e.g. to highlight small but important differences in perspective or to explore common ground).

When first thinking about data stories, we had several discussions with participants about what data stories do, how they were often used in the context of advocacy and policy work to (for example) persuade people, to move people, to convince people to do things. But we also returned to the questions of “which people?” and “what should they do?”. Are local data stories for drivers or decision-makers, citizens or companies, lobbyists or activists? How might these characters feature in these stories? What work do these stories do? Might there be unexpected consequences? For example, commented that too much of a focus on the action of individual citizens might obscure or detract attention from other structural or systemic issues (e.g. national laws or large corporate polluters). Conversely portraying it as an issue that only big polluters or politicians could deal with, the significance of other types of collective action could be underplayed. Part of our hope through the Hot Potato Machine was to pay attention to how different actors view air pollution as an issue through the lens of who they consider responsible by comparing and contrasting their accounts.

We were also very interested in what these accounts could do – not just in terms of what they tell people, but how they might involve people in their co-production. There are all kinds of potential issues with how stories about responsibility might be told. Stories about how action is symmetrically gridlocked might risk making it seem like there is no space for movement. Stories based on prominent public sources risk amplifying dominant messages and neglecting actors whose views are less explicit or publicly visible online. While the process of assembling claims can be time consuming and the design decisions can be difficult, the reward for participating in the process is a rich acquaintance with the social life of air pollution as an issue.

Next steps and requirements for the project

We are particularly interested in how to facilitate public involvement around the data gathering process, and to make open source templates and components which would enable others to undertake their own explorations of who considers whom to be responsible for what in relation to air pollution (as well as other issues).

We would like to continue to explore how the Hot Potato Machine can be used for teaching, research and experiments in participation around air pollution involving universities, activists, journalists and local administrations.

References

- ADDY, S.O. 1888. A Glossary of Words Used in the Neighbourhood of Sheffield. London: Trubner & Co. for the English Dialect Society.

- BARNES, J.H., Hayes, E.T., Chatterton, T.J. and Longhurst, J.W.S. 2017. Policy disconnect: A critical review of UK air quality policy in relation to EU and LAQM responsibilities over the last 20 years. Under consideration for publication in Environmental Science & Policy. Retrieved from http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/30183.

- CARRINGTON, D. and Mason, M. 26 July 2017. Government’s air quality plan branded inadequate by city leaders. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jul/26/governments-air-quality-plan-is-cynical-headline-grabbing-say-critics.

- BARRETT, S., Colthrorpe, T., Wedderburn, M. 2017. Street Smarts: Report of the Commission on the Future of London’s Roads and Streets. Centre for London. Retrieved from https://www.centreforlondon.org/publication/street_smarts_report_of_commission_londons_roads_and_streets/.

- CLIENTEARTH. 2017. Gove falls at first hurdle on air pollution, say environmental lawyers. Retrieved from https://www.clientearth.org/gove-falls-first-hurdle-air-pollution-plans-environmental-lawyers/.

- LATOUR, B. 2007. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION. 2018. LGA responds to Select Committee report on air quality. Retrieved from https://www.local.gov.uk/about/news/lga-responds-select-committee-report-air-quality

- OWEN, B.B., Cooke, L and Matthews, G. 2013. The development of UK government policy on citizen’s access to public sector information. Information Politicy 18: 5-19.

- PORTER, T. 2012. Thin Description: Surface and Depth in Science and Science Studies. Osiris. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/667828

- ROGERS, R. n.d. List Making Associative Query-Snowballing Technique. Amsterdam: Digital Methods Initiative. Retrieved from http://www.govcom.org/DigitalMethods/DMI%20Listmaking%20and%20associative%20query%20snowballing.pdf

- ROGERS, R. (2013). Digital Methods. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.